Modern biosciences are developing so rapidly that ethical evaluation can no longer keep pace. Transgenic plants, vaccines, personalized medicine, huge databases containing highly personal information—do we need all of this, or should we pause for a moment and carefully examine all the possible consequences first? The question goes far beyond philosophical aspects and should include practical considerations regarding health, nutrition, and sustainability, as well as the impact on innovation potential, the economy, and competition.

The following article was written by a “couch philosopher” who sees more questions than answers in the ethical debate. I would like to encourage discussion of ethical considerations in the context of practice and the consequences for our society, and I look forward to your constructive comments.

Why is genetic data both important and ethically controversial?

This article is based on a question from the audience at ICOBIOS in Malang, Indonesia, on October 25, 2025, where I had the privilege of giving one of the keynote speeches on “Genes, Genomes, and Metagenomes.” Afterwards, one participant asked, “What ethical problems do you see in the comprehensive collection of personal genetic data?”

This is a very valid question. The amount of information that can now be derived (more or less reliably) from genetic data is enormous. DNA and RNA analyses allow increasingly accurate predictions about genetically determined disease risks and current infectious diseases. In an earlier blog article, we reported on initial attempts to derive a “mug shot” from a DNA trace at a crime scene (https://www.biowisskomm.de/2022/11/phantombilder-aus-dna-analyse/). Air filtrates can be used to determine who has been in a room by means of DNA sequencing https://www.scinexx.de/news/biowissen/erster-nachweis-von-dna-aus-der-luft/ . Allegedly, high-ranking politicians take meticulous care not to leave any DNA traces at conferences. They could provide clues about personal characteristics or illnesses, or even enable “personalized” assassinations. Whether politicians can control their breath and skin abrasions is, however, rather questionable.

Is it even possible to reliably regulate the collection and evaluation of such data, e.g., by government institutions, insurance companies, employers, and others?

On the other hand, this data is indispensable if we want to understand diseases and develop therapeutics.

Data naivety or a contribution to research?

It is remarkable that approximately 15 million customers of the company 23andMe sent their DNA for analysis and even paid money for it. 80% of customers agreed to the use of their data for research purposes, but other uses are not excluded. In 2023, 23andMe was hacked. Seven million data records (including personal information) were stolen and presumably sold on the dark web.

Absolute data security can never be guaranteed. It is doubtful whether all customers are aware of the possible consequences, despite of mandatory, comprehensive information.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28805093

Another company is MyHeritage, which also offers microarray analysis, but now also whole genome sequencing. I find it almost macabre that DNA sequencing is being offered in a Black Friday Sale. Several other companies have similar offers. Personal information has become a commercial product.

In principle, it is already possible to perform complete DNA sequencing in any “kitchen laboratory” with some basic knowledge of molecular biology and bioinformatics and equipment worth €2,000 to €3,000. Control or regulation will soon be virtually impossible. It is particularly problematic to leave customers and users alone with data that provides information about genetic diseases. In most cases, they will hardly be able to interpret the data correctly without professional guidance and may come to the wrong conclusions if a predisposition to a hereditary disease is detected.

Big data and data protection

Complete protection of sensitive data can never be guaranteed. The sensitivity of individual genetic data is obvious. There are various ways in which it could be misused: insurance companies could factor genetic risks into their premiums, employers could reject applicants on the basis of genetic predispositions, certain genetic traits could lead to discrimination. This raises countless ethical problems and questions: If someone knows they have a genetic predisposition for a serious illness, are they allowed to conceal this from an insurance company? Are they allowed to buy a high-value life insurance policy? Must a pilot or bus driver report any genetic risks they are aware of (e.g., mental illness or cardio-vascular condition) to their employer? Is it allowed to require an employee to undergo genetic testing in order to minimize risks for themselves and their customers? Should genetic analysis be recommended before conceiving a child in order to prevent the spread of genetic diseases? (This has actually been practiced for decades in the world’s largest eugenics program.)

The increasing amount of data has led to several updates in data analysis at 23andMe alone. More relevant gene variants have been identified, as well as more genes that are candidates for diseases or mental health issues, intolerances, resistances, and other conditions. The information content of genotyping is constantly increasing.

At the same time, the pharmaceutical industry is utilizing this data to develop drugs and therapies. For example, in June 2025 a 6-month old baby was treated with a personalized gene therapy for a liver disease. It took six months to detect the genetic mutation, develop the treatment, test it in cell culture and animal experiments and get the permission for a first clinical trial. So far, the treatment appears to be successful. All this was based on genetic data.

Is it permissible to use data that has been collected under ethically questionable conditions?

For a long time, the rule in science was that research data (anonymized if necessary) should be publicly accessible and shared internationally. This system has become flawed. Controversial DSI (digital sequence information) legislation aims to give countries exclusive rights to their DNA sequence data, meaning that genetic data will disappear behind a paywall and countries will determine who has access to it and at what price (this applies to sequence data from humans, animals, plants, and microorganisms).

We do not necessarily know what data is collected by companies and in countries with less transparent science.

Due to differing legislation, we also do not always know what ethical rules were used to collect even publicly available data and results. Are we even allowed to use such data with unclear or questionable origins?

One example of this is the three “CRISPR babies” born in China in 2018. The experiment, in which the CCR5 gene was “cut off” by germ line genetic engineering, was (by our rules) beyond all ethical standards. As a result, several major scientific journals refused to publish the work. On the other hand, scientist He Jiankui is accused of never having published the experiments.

Which experiments and medical procedures are legal or illegal in other countries and cultures varies depending on the legislation: the production of embryonic stem cells is prohibited in Germany, but not in Israel. Surrogate motherhood is permitted in many countries, but not in Germany. He Jiankui’s experiments were generously funded by the Chinese state, which only later, when there was worldwide outrage, officially distanced itself from them. At the same time, no more information on the well-being of the children was released.

It is conceivable that the CRISPR baby experiment has failed completely, that the children have suffered serious damage or have already died. This would probably lead to further experiments being suspended (at least temporarily).

Or the experiment was a complete success, despite all its technical shortcomings. Regardless of ethical concerns, this would probably accelerate ambition and the desire to do further experiments in some laboratories.

It is almost certain that the genomes of the three children have now been completely sequenced. China will also know whether the expected results (improved neuroregeneration, improved memory, and HIV resistance) have been achieved or not (https://www.biowisskomm.de/2024/11/die-optimierung-des-menschen/).

Do we want to, are we allowed to, or do we have to know these results?

Symbolic picture generated by AI.

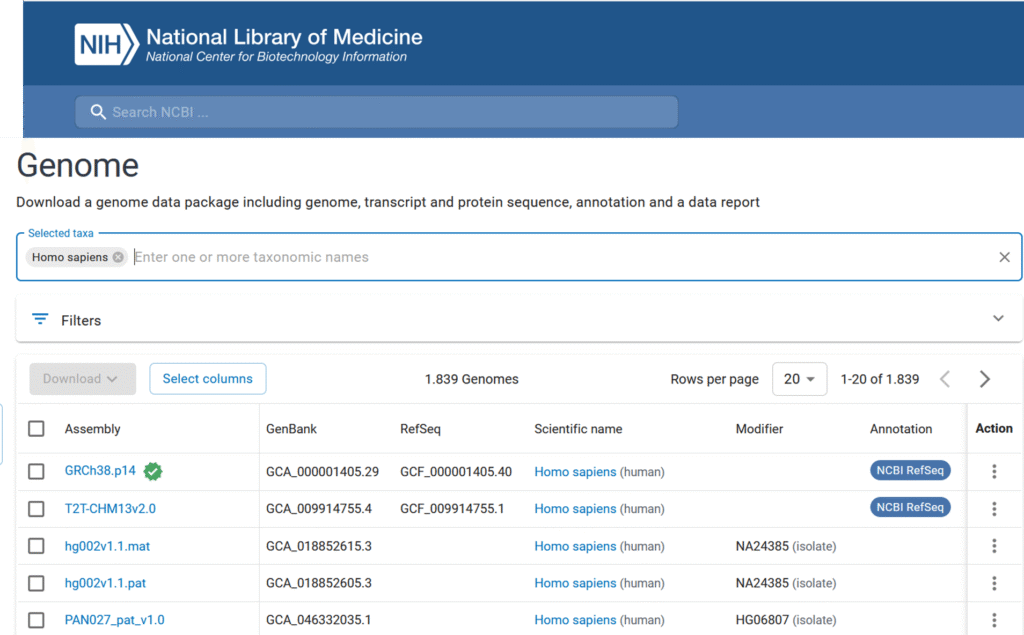

More is better – when it comes to sequence data, quantity is key.

The wealth of data brings ethical risks, but at the same time it is an indispensable prerequisite for medical progress.

DNA sequencing has long since ceased to be “rocket science.” With inexpensive equipment (starting at €1,000) and a little know-how, billions of DNA bases can be sequenced within a few hours.

Volume is important. The more data there is, the better the significance between certain DNA sequences variants and the expression of a certain trait (such as a hereditary disease). This then opens up possibilities for developing therapies that can be tailored to rare mutations in some cases.

Those who have a lot of data reach their goal faster. Countries with less stringent regulations can accumulate more data more easily, quickly, and cheaply. And it is certainly also easier to “try out” therapies under ethically questionable conditions. So-called “rare diseases” (affecting fewer than 5/10,000 people, some of which are significantly rarer) pose a major challenge in terms of finding their genetic origin.

Another challenge is multi-gene diseases, i.e., the interaction of several mutations is required for a disease to become manifest. Here, too, very large amounts of data are required to track down such interactions.

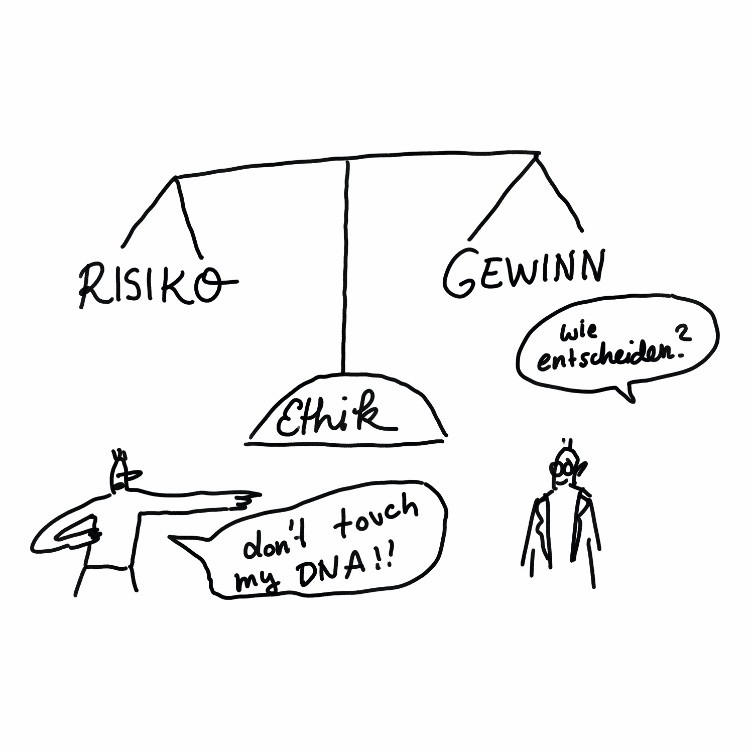

Can the ethical dilemma be resolved?

If, for example, you want to protect personal data as securely as possible and collect data in an ethically sound manner, this makes research more complicated and costly. The same applies to clinical trials and animal testing. Extensive approval procedures and organizational measures are required. This is widely accepted in our society, but other societies have different rules and ethical standards.

Strict ethical rules create scientific disadvantages: more time and money are needed, and some experiments cannot be carried out at all. This does not mean that the rules should be thrown out. However, we must be aware of this and find solutions that allow us to keep up with intellectual and economic competition. And we must consider the conflicts that will undoubtedly arise from different ethical standards.

If, for example, China develops new drugs and therapies, will their approval in Europe be made dependent on the ethical conditions of data collection and product development? Will the development be documented transparently enough to be able to assess this? On the other hand, would it be ethically justifiable to deny sick people a functioning drug because its development did not meet our ethical standards?

In addition to this, there is a huge the gap between the rich and the poor: should medical treatments be approved if not everyone has equal access to them? Wealthy people will always find more or less legal ways to get treatment abroad. Should one deny a life saving treatment to them just because they are rich and others are not?

Priority for ethical standards?

It could be argued that ethical standards have the highest priority, regardless of scientific success or failure. In the case of drugs that have been developed under ethically questionable conditions, however, this raises a new ethical problem: it is questionable whether doctors are acting in accordance with the Geneva Declaration (the modern version of the Hippocratic Oath) when they refuse to provide a patient with a curative therapy. Are patients or their relatives acting unethically when they demand a drug that cures or alleviates suffering? Or are doctors and relatives acting unethically when they accept a patient’s suffering for ethical reasons?

Another way of thinking about this would be to engage in dialogue with other countries and cultures and ultimately convince them of our ethical views. I doubt that such “proselytizing” is appropriate. It implies the superiority of our ethics over other cultures and, in extreme cases, can be interpreted as denying them ethical competence.

If we want to maintain our scientific competence and expertise on the one hand and our ethical standards on the other (we are ethically obliged to do both, in my opinion), we must redouble our efforts and deliver excellence and innovation despite all the hurdles we have set ourselves. An eloquent “master teacher” who simultaneously demonstrates that his ethical maxims do not lead to innovations for the benefit of humanity is not someone to look up to.

It is becoming increasingly difficult. Other countries, especially China, have caught up enormously in terms of both scientific competence and technological know-how and are now at least on a par with the formerly leading scientific nations. We must accept this challenge.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version) with modifications by the author.

Acknowledgement

I thank Jann Buttlar for critical comments on the manuscript. Many, but not all of his suggestions have been included.

Disclaimer

This article represents the personal views of the author. It does not claim to take all aspects into consideration but is rather intended to stimulate discussion.

Author

Wolfgang Nellen, BioWissKomm